TS Eliot’s Four Quartets

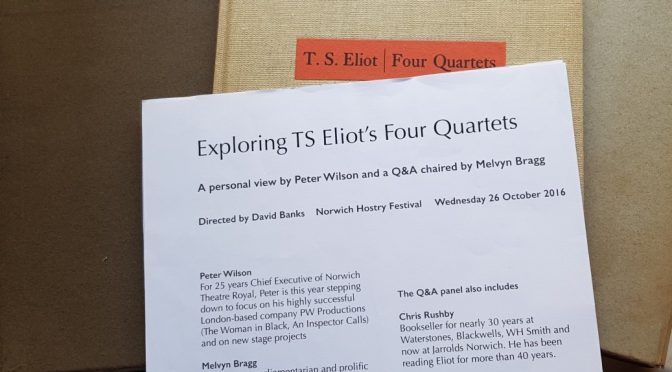

As part of the Norwich Hostry Festival, it was a privilege to both hear Peter Wilson‘s reflective rendition of the four-part poem by T S Eliot and to be on a literary panel chaired by Melvyn Bragg discussing the Four Quartets after.

“Love is most nearly itself

When here and now cease to matter.

Old men ought to be explorers…”

The full panel consisted of Peter Wilson – Chief Executive of Norwich Theatre Royal; David Banks – actor, author and director, Chris Rushby – Blackwells and Waterstones to Jarrolds bookseller and 40-year passionate explorer of Eliot; Katy Jon Went – amateur hack and commentator; and Eve Stebbing – EDP and Daily Telegraph theatre critic, and founder of Spin-Off Theatre.

I previously ‘paneled’ with David Banks on the Hostry Festival play discussion of his Five Marys Waiting (2012). This time I sat next to Chris Rushby, both during the poems’ reading and also during the discussion, and I think we exchanged looks after as we felt an emotional punch to the gut at the end of the recitation, which was more of a reflection and internal dialogue with self. The delivery was very personal and searching.

It’s been years since I’ve read Eliot at length – apart from Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats (1939), probably the last time was at school! But recently I heard these lines:

“We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.”

They draw me back to the poem and the digging out of a 1968 Folio Society edition, in search of where they were among the lines.

Indeed, I rang my father the night before the panel, asking for the potted York Notes precis of its meaning. Needless to say, he began by quoting The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1915):

“Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table;”

Before he could get stuck into The Wasteland (1922) and “April is the cruellest month”, I asked him to fast forward to 1935 and to Burnt Norton, the first of the Four Quartets.

Just as I expected, though, it was an emotional and sensual response that my father relayed, not a critical-academic one, and rightly so, for that was the reaction of most of us on the panel. It meant any analysis of literary and religious allusions, or of George Orwell’s criticisms at its lack of deep despair, or too much reliance on god and spirituality was somewhat redundant.

It was, however, The Wasteland, that began Eliot’s poetical-theological journey into not only Anglo-Catholicism – to which he publicly converted in 1927, but also Hinduism and Buddhism, as well as Greek philosophers and poets.

“I see the path of progress for modern man in his occupation with his own self, with his inner being” – TS Eliot

Eliot was fascinated with spiritual search and one’s psychological journey, not to mention temporal and historical reflections. Time, especially, is a recurring theme in the Four Quartets, time and not-time, time past and time future, incarnate and potentate in time present, that is:

“Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future

And time future contained in time past.

If all time is eternally present

All time is unredeemable.”

Unlike the New Testament call to “redeem the time”, for Eliot, time needs no redeeming because it is not lost, it is always with us, in the moment. Indeed, Eliot’s thoughts presage modern concepts of mindfulness and being in the moment, which in turn hark back to older Buddhist appreciations.

Possibility is neither abstraction or a speculation, but an ever-present power in what already is.

“What might have been is an abstraction

Remaining a perpetual possibility

Only in a world of speculation.

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.”

Footfalls echo in the memory

Down the passage which we did not take

Towards the door we never opened”

Journeying is a strong theme in the Four Quartets, but one where arrival or purpose are as intangible as time.

“And what you thought you came for

Is only a shell, a husk of meaning

From which the purpose breaks only when it is fulfilled

If at all. Either you had no purpose

Or the purpose is beyond the end you figured

And is altered in fulfilment. There are other places

Which also are the world’s end, some at the sea jaws,

Or over a dark lake, in a desert or a city—

But this is the nearest, in place and time,

Now and in England.”

In all of Eliot’s expressed contrasts and even contradictions in the Four Quartets, meaning, if it can found at all, is not discovered at the poles but at the intersections.

“The tolling bell

Measures time not our time, rung by the unhurried

Ground swell, a time

Older than the time of chronometers, older

Than time counted by anxious worried women

Lying awake, calculating the future,

Trying to unweave, unwind, unravel

And piece together the past and the future,

Between midnight and dawn, when the past is all deception,

The future futureless, before the morning watch

When time stops and time is never ending;

And the ground swell, that is and was from the beginning,

Clangs

The bell.”